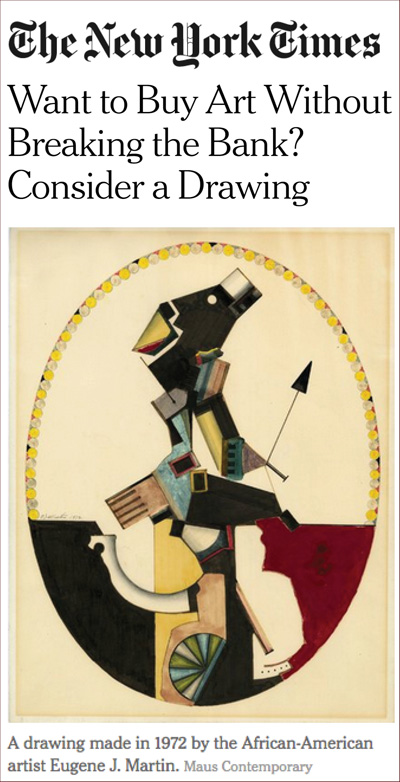

Maus Contemporary

Darker Than Blue (image: Willie Cole, Double-You-See, detail, 2017) Darker Than Blue (image: Willie Cole, Double-You-See, detail, 2017) |

Darker than Blue

Willie Cole, Coco Fusco, Lonnie Holley, Charlie Lucas, Eugene James Martin, Taj Matumbi, Lorraine O'Grady, Bayeté Ross Smith, Leslie Smith III, Hank Willis Thomas, and Della Wells

|

scoll down for complete exhibition checklist

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

"Darker than Blue" installation view

exhibition checklist in alphabetical order

Willie Cole

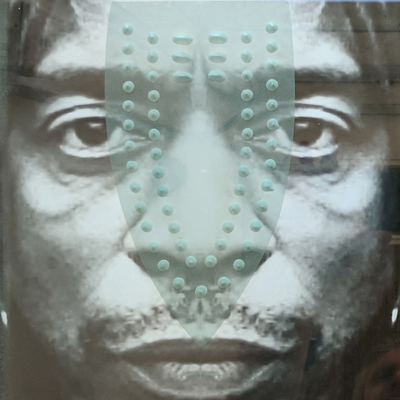

Willie Cole "Double-You-See", 2017

Willie Cole "Double-You-See", 2017

Willie Cole Double-You-See

2017

two photographs, self portraits of the artist, shown behind sandblasted glass,

two individual panels, displayed on white, wooden shelf, the glass panels' top sections leaning against the wall

each panel approx. 13 by 10 by 0.75 in. (ca. 33 by 25,4 by 1,9 cm)

installed approx. 12 by 24 by 4 in. (ca. 30,5 by 61 by 10,1 cm)

Willie Cole "Double-You-See" installation view

Willie Cole "Double-You-See" installation view

Willie Cole "Double-You-See" installation view

Willie Cole "Double-You-See" installation view

Double-You-See was included in the 2018 exhibition Portraits of Who We Are at the David C. Driskell Center For The Study Of Visual Arts & Culture Of African Americans & The African Diaspora at the University of Maryland.

Double-You-See is unique work, and relates to the artist's seminal 1998 piece G.E. Mask and Scarification, illustrated and discussed in the publication "Anxious Objects: Willie Cole's Favorite Brands" (pages 68, 69, and front cover), published in 2006 by the Montclair Art Museum, distributed by Rutgers University Press.

Willie Cole "Bronx Bambi", 2015

Willie Cole "Bronx Bambi", 2015

Willie Cole Bronx Bambi

2015

shoes, nylon thread, stainless steel wire, screws

approx. 22 by 17 by 11 in. (ca. 56 by 23 by 48 cm)

Willie Cole "Goldylicks", 2015

Willie Cole "Goldylicks", 2015

Willie Cole Goldylicks

2015

shoes, nylon thread, stainless steel wire, screws

approx. 17 by 15.25 by 8.25 in. (ca. 43 by 28,8 by 21 cm)

Coco Fusco

Coco Fusco "They Are Too White To Be Indians", from the artist's "The Undiscovered Amerindians" series, 2012

Coco Fusco "They Are Too White To Be Indians", from the artist's "The Undiscovered Amerindians" series, 2012

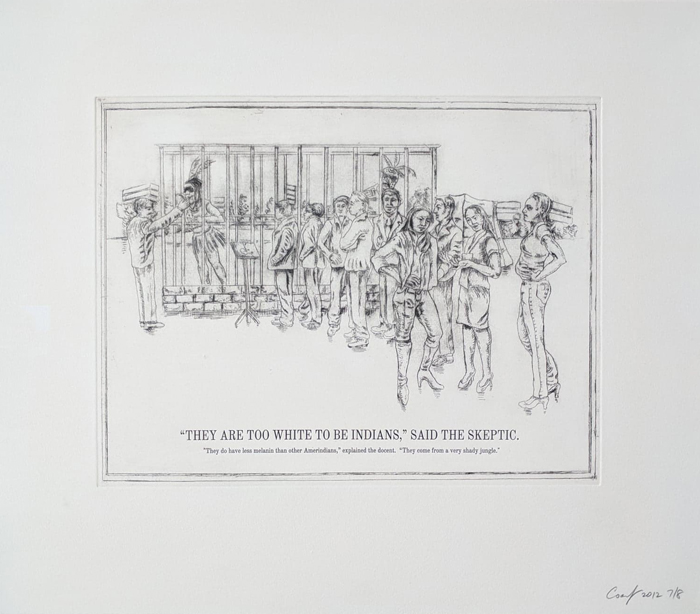

Coco Fusco

The Undiscovered Amerindians; "They Are Too White To Be Indians," said the Skeptic

2012

intaglio, engraving, and drypoint etching on paper, #7/8 of an edition of 8

approx. 18.25 by 21 in. (ca. 46,3 by 53,3 cm)

provenance: Alexander Gray Associates, New York

private US collection

"THEY ARE TOO WHITE TO BE INDIANS, " SAID THE SKEPTIC.

"They do have less melanin than other Amerindians," explained the docent. "They come from a very shady jungle."

2012 marked the twentieth anniversary of Fusco’s seminal collaborative performance work with Guillermo Gomez-Peña, Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West and its presentation in the legendary 1993 Whitney Biennial.

Fusco revisited this important work through a series of engravings. Rendered in the style of Nineteenth-century caricatures, Fusco’s recollections of audience responses to the Amerindians performance weaves a humorous yet unsettling narrative, exposing the residue of colonial stereotypes in contemporary culture. While looking back, these works underscore the long-lasting effects of colonialism that remain prevalent in the contemporary art world, in spite of broad cultural progress since the early 1990s platforms of institutional-critique and multiculturalism.

Coco Fusco (b.1960), interdisciplinary artist and writer, explores the politics of gender, race, war, and identity through multi-media productions incorporating large-scale projections, closed-circuit television, web-based live streaming performances with audience interaction, as well as performances that actively engage with audiences. Over the past twenty-five years, Fusco has investigated the ways that intercultural dynamics affect the construction of the self and ideas about cultural otherness. Her work is informed by multicultural and postcolonial discourses as well as by feminist and psychoanalytic theories, yielding art projects about ethnographic displays, animal psychology, sex tourism in the Caribbean, labor conditions in free trade zones, suppressed colonial records of indigenous struggles, and military interrogation in the War on Terror. Much of her recent work focuses on Cuban culture in the post-Communist era.

please contact Alexander Gray Associates to learn more about Coco Fusco and see available work

![]() click to visit Alexander Gray Associates

click to visit Alexander Gray Associates

Lonnie Holley

Lonnie Holley "Running Out Of Time", 2008

Lonnie Holley "Running Out Of Time", 2008

Lonnie Holley

Running Out Of Time

2008

mixed media on wood panel

approx. 96 by 48 in. (ca. 243,8 by 121,9 cm)

provenance: Art/Folk Birmingham, AL, the artist's studio

private US collection

| My mother's name was Dorothy May Holley Crawford. My father's name was Arthur James Bradley. When I was born this lady asked my mom could she keep me, because my mom already had another baby. So the lady took me away from my mama and took me to Ohio, and she kept me up there until I was four years old. Then she brought me back to Birmingham, Alabama. She brought me out near the fairgrounds, and the lady sold me to another lady for a pint of whiskey. I was a malnourished, skinny little baby with a big, big head. They called me "Tank" for awhile—"Tankhead." I had a real big head. I ended up with a lady I called "Big Mama." Big Mama was nice. Big Daddy wasn't. I remember that when I was seven years old, Big Mama died. I didn't know what death was at seven years old. Every morning I would get up and go to school. I would fix her some food and leave it there on the side of the bed, 'cause he was working at night and he told me to watch her till I got ready to go to school, and make sure I left her food to get. So she had died and I didn't know it, and he hadn't come home that night. He didn't come home the next day. So she laid there dead for about three days. He came in and he had whiskey on his breath. And he asked me how Big Mama was doing, and I told him she hadn't ate for the last three days, and I couldn't get her to move. He asked me if she had used the bathroom in the bed, and I told him no, she hadn't did nothing. So he went in there and shut the door. And I heard him start hollering. He was running and shouting, and he was screaming, "She's dead, she's dead," and I'd never even heard that word. And then he came out fussing at me, how come I didn't let somebody know she was dead. So I got punished for not knowing what death was, and I got a whipping, and didn't know how to handle that. And I was sad. He had the radio playing. And he had this record on: "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, Coming for to Carry Me Home." I remember the undertaker coming, and the undertaker was getting ready to take her away, so he put this record on: "Undertaker, undertaker, please drive slow / 'Cause this body that you're carrying, sure hate to see it go." I remember these things—that these were things that hurt. (…)

transcribed from audio recordings made by the artist in 1994 and 1995 read the entire transcript on SoulsGrownDeep.com

The Souls Grown Deep Foundation advocates the inclusion of Black artists from the South in the canon of American art history and fosters economic empowerment, racial and social justice, and educational advancement in the communities that gave rise to these artists. Souls Grown Deep derives its name from a 1921 poem by Langston Hughes (1902-67) titled The Negro Speaks of Rivers, the last line of which is "My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” The Souls Grown Deep Foundation stewards the largest and foremost collection of works by Black artists from the Southern United States, encompassing some 1,000 works by more than 160 artists, two-thirds of whom are women. The Foundation advances its mission through collection transfers, exhibitions, education, public programs, and publications.

Please donate to the Souls Grown Deep Foundation if you can.

|

Lonnie Holley "Up and Down in Alabama", 2008

Lonnie Holley "Up and Down in Alabama", 2008

Lonnie Holley "Up and Down in Alabama", 2008

Lonnie Holley "Up and Down in Alabama", 2008

Lonnie Holley

Up and Down in Alabama

2008

mixed media

approx. 30 by 15 by 15.5 in. (ca. 76,2 by 38,1 by 39,4 cm)

provenance: Art/Folk Birmingham, AL, the artist's studio

private US collection

Lonnie Holley talking about "Up and Down in Alabama", Art/Folk exhibition "Lonnie Holley Studio Visit", Birmingham, Alabama, 2008

Lonnie Holley talking about "Up and Down in Alabama", Art/Folk exhibition "Lonnie Holley Studio Visit", Birmingham, Alabama, 2008

Lonnie Holley "Up and Down in Alabama", 2008

Lonnie Holley "Up and Down in Alabama", 2008

Charlie Lucas

Charlie Lucas "Music Calm the Savage Beast", ca.1987

Charlie Lucas "Music Calm the Savage Beast", ca.1987

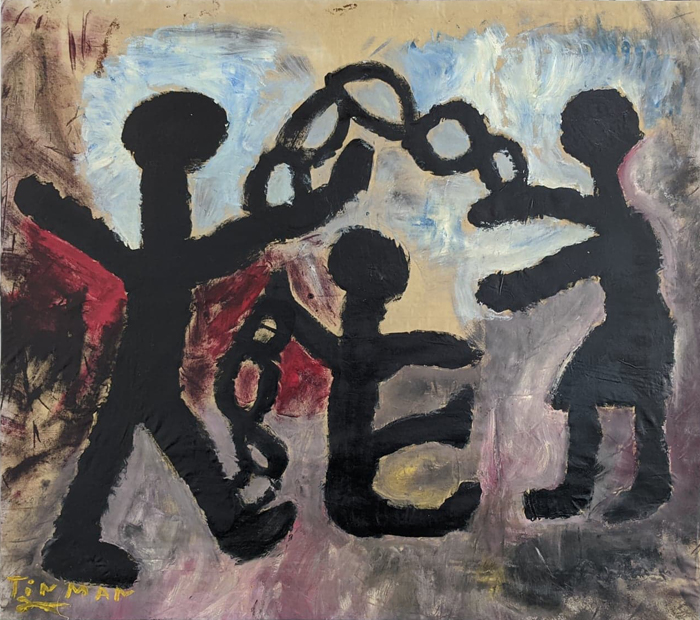

Charlie Lucas

Music Calm the Savage Beast

ca. 1987

mixed media on wood panel, signed CL on front, titled on back

approx. 23 by 61 in. (ca. 58,4 by 154,9 cm)

Music Calm the Savage Beast was included in the 2021 exhibition Charlie Lucas Talking to the Ancestors at the Paul R. Jones Museum at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

Charlie Lucas "Crawling Out (Venice, Italy)", 2011

Charlie Lucas "Crawling Out (Venice, Italy)", 2011

Charlie Lucas

Crawling Out (Venice, Italy)

2011

enamel, acrylic, and charcoal on stretched canvas (*)

approx. 47.5 by 55.25 in. (ca. 120,6 by 140,3 cm)

The painting Crawling Out was created in Venice for the exhibition The Roots of the Spirit organized and curated by Martha Henry during the 2011 Venice Biennale (which also featured Lonnie Holley, Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warmack), and Kevin Blythe Sampson).

Charlie Lucas "Taking the Spirit Loose and freeing It (Venice, Italy)", 2011

Charlie Lucas "Taking the Spirit Loose and freeing It (Venice, Italy)", 2011

Charlie Lucas

Taking the Spirit Loose and freeing It (Venice, Italy)

2011

enamel, acrylic, and charcoal on stretched canvas (*)

approx. 47.25 by 53.5 in. (ca. 120 by 135,9 cm)

The painting Taking the Spirit Loose and freeing It was created in Venice for the exhibition The Roots of the Spirit organized and curated by Martha Henry during the 2011 Venice Biennale (which also featured Lonnie Holley, Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warmack), and Kevin Blythe Sampson).

Taking the Spirit Loose and freeing It was also included in the 2021 exhibition Charlie Lucas Talking to the Ancestors at the Paul R. Jones Museum at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa.

The artists, Lonnie Holley, Mr. Imagination, Charlie Lucas, and Kevin Sampson were invited by the American Folk Art Museum (funded with the generous support of the Ford Foundation) and Benetton to create large, site specific installations as the first exhibition in Benetton’s newly acquired Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice to open on June 1, 2011 during the Venice Biennale. The inclusion of four African American self-taught artists during the 54th Venice Biennale would have been revolutionary because the artists, who have been historically excluded from the American art canon, would have had the opportunity to exhibit within a broader contemporary art dialogue during the world’s largest art event. Unfortunately this potentially groundbreaking exhibition was abruptly canceled two weeks before the artists were to depart for Venice.

The four artists and I, as curator, decided to travel to Venice anyway to create an exhibition during the Biennale even though we had no materials and financial support.

L’Espace Re-Evolution offered these American artists the opportunity to create an exhibition in less than one week in one of the most beautiful spaces in Venice, a 1000 year old garden located on the Zattere on Dorsoduro next to the Vedova Foundation and near the Pinault and Guggenheim collections. Limited by time and working with only materials they found on the streets and in the waters of Venice, the four artists created almost 50 site specific works that respect the Venetian spirit of this special place.

Lonnie Holley combined sculptures with paintings that read as a diary of his sojourn. The ghostly appearance of Mr. Imagination’s silver wire mesh dress and shoes alluded to the garden’s secret past. Charlie Lucas painted two works on bed sheets (*) that are consistent with his philosophy of art and life. Kevin Sampson created an ephemeral wall installation of grottoes and shrines using seaweed and bones in an attempt to connect the past with the present.

- Martha Henry, 2011

(*) The two paintings Crawling Out and Taking the Spirit Loose and freeing It were created in Venice for the exhibition The Roots of the Spirit organized and curated by Martha Henry during the 2011 Venice Biennale (which also featured Lonnie Holley, Mr. Imagination (Gregory Warmack), and Kevin Blythe Sampson).

Charlie Lucas in his home in Pink Lily, Alabama, April 10 2011

Charlie Lucas in his home in Pink Lily, Alabama, April 10 2011

Charlie Lucas in his home in Pink Lily, Alabama, April 10, 2011

Eugene James Martin

Eugene James Martin "Jockey", 1968 - installation view

Eugene James Martin "Jockey", 1968 - installation view

Eugene James Martin "Jockey", 1968

Eugene James Martin "Jockey", 1968

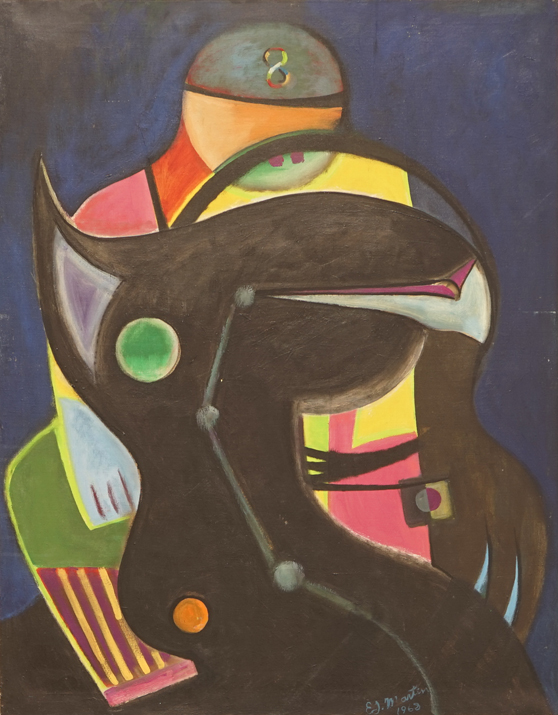

Eugene James Martin

Jockey

1968

oil on canvas, artist frame

approx. 42 by 33 in. (ca. 106,7 by 83,8 cm)

Eugene James Martin "Untitled", 1969 - installation view

Eugene James Martin "Untitled", 1969 - installation view

Eugene James Martin "Untitled", 1969

Eugene James Martin "Untitled", 1969

Eugene James Martin

Untitled

1969

oil on canvas, artist frame

approx. 40 by 33.75 in. (ca. 101,6 by 85,7 cm)

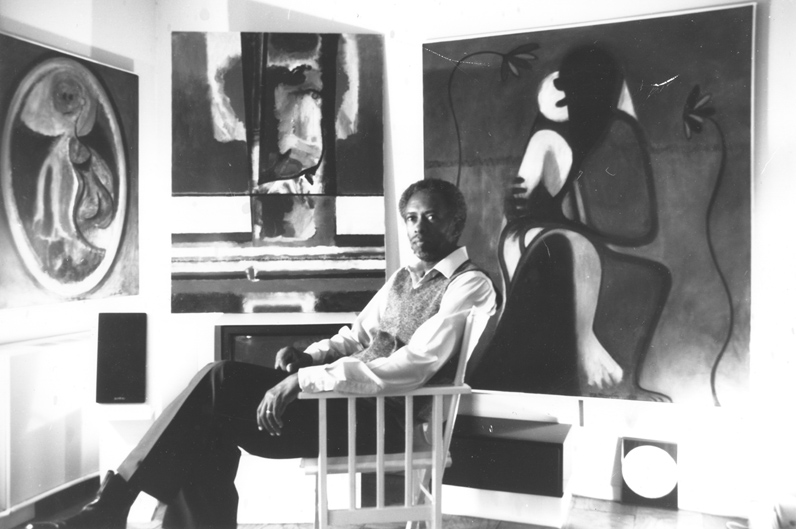

| Eugene James Martin (Washington, DC, 1938 - Lafayette, LA, 2005) is known for his often gently humorous works that may incorporate whimsical allusions to animal, machine and structural imagery among areas of “pure”, constructed, biomorphic, or disciplined lyrical abstraction. Martin called many of his works straddling both abstraction and representation “satirical abstracts”. His work is included in numerous Museum collections, including the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA; the Alexandria Museum of Art, Alexandria, LA; the Stowitts Museum and Library, Pacific Grove, California; the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, NY; the Paul R. Jones Collection of African American Art, University of Delaware, Newark, DE; the Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, AL; the Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, NE; the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, MS; the Masur Museum of Art, Monroe, LA; the Louisiana State University Museum of Art, Baton Rouge, LA; the Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art, Savannah, GA; and the Munich Museum of Modern Art in Munich, Germany. |

|

| Eugene James Martin in his studio, Washington, DC, 1988 |

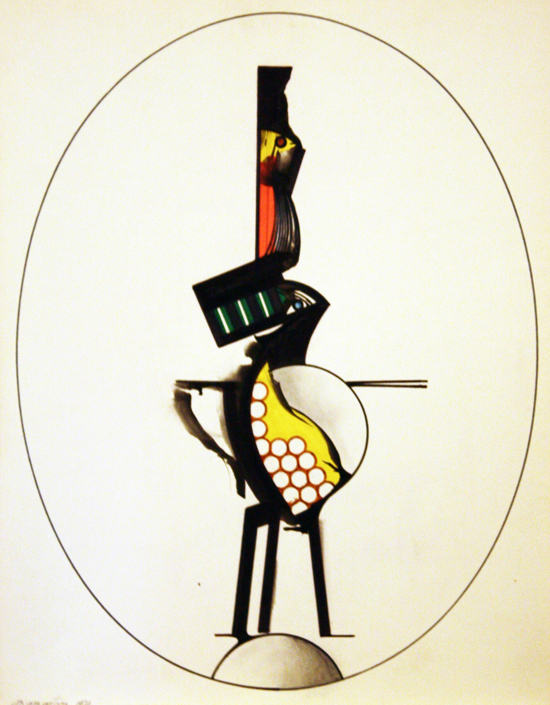

Eugene James Martin work on paper, 1971

Eugene James Martin work on paper, 1971

Eugene James Martin

Untitled

1971

ink on paper

approx. 15.75 by 12 in. (ca. 40 by 30,5 cm)

Eugene James Martin work on paper, 1971

Eugene James Martin work on paper, 1971

Eugene James Martin

Untitled

1971

ink, gouache , black marker, and graphite on paper

approx. 15.5 by 12 in. (ca. 39,4 by 30,5 cm)

Black artists may have been marginalized, but one can no longer dismiss them as outsiders. They have been as central to Abstract Expressionism as Norman Lewis or Charles Alston and as central to the shaped canvas of the 1960s as Al Loving or Sam Gilliam. They have been as central to the space between abstraction and representation as Hale Woodruff or Beauford Delaney. They have been as central to the full recognition of women artists as Howardena Pindell or Alma Thomas, and they are central to art today.

The distinction takes on special urgency for a black Southern artist only now gaining his due, Eugene James Martin. Martin almost fits the fashion for outsider art, and if that will help others discover him, terrific. Yet nothing is half as naïve as it may seem. Born in 1938, Martin studied at the Corcoran in Washington, D.C., and his work makes plain his knowledge of Cubism, including its spatial density and collage technique. Yet he also knew the bolder colors and outlines of postwar American art. His drawings, in overlapping curves of graphite or pen and ink, treat black and sepia as the rich colors they are for him as well. He started out playing jazz, and one could call that a key influence, too. He worked quickly in both acrylic and collage, like a born improviser bouncing off others in a band. Martin sometimes described his art as satirical abstracts, knowing full well that it is not at anyone’s expense. Yet the label does get at the seriousness, the comedy, and the eclecticism. For him, art cannot leave personal experience behind. That may be why a figure keeps making an appearance in Martin’s work, even at its most abstract, and to judge by early titles like Detective Jones or Food and Drugs, he could be on either side of the law.

Now that abstraction is back, big time, but often touched by representation, Martin’s questioning is newly relevant. Like many younger artists, he might have leaped straight from the clarity of an earlier Modernism to American Pop Art and the graphic novel, while some of those floating fields of color do have a parallel in Hans Hoffman. One can see him putting abstraction through its paces, but with plenty of interruptions along the way. Paintings from the 1990s, just before and after Martin moved to Louisiana, have a newfound energy, but also a greater simplicity. Their ground now looks like a grid, although a line of one color might leap across a rectangle, over a brushier green, to land on the other side. In his last years, before his death in 2005, his art becomes sparer, purer, and also less regular. Its subject might be a single descending brushstroke, but then Martin’s real subject was painting all along. And painting here begins and ends with abstraction.

Black Southern art can hardly avoid questions of identity in those enigmatic figures and the space in which they live, and Martin’s color contrasts resemble those of Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden. Yet that just adds to the ongoing riddle of whether one can distinguish an African American abstraction—and how. One might look for answers starting here.

Eugene James Martin "Slap Happy", 1984-87

Eugene James Martin "Slap Happy", 1984-87

Eugene James Martin

Slap Happy

1984-87

ink, colored pencil. graphite, and acrylic on paper

approx. 13.25 by 10.25 in. (ca. 33,8 by 26,3 cm)

Taj Matumbi

Taj Matumbi "Self Portrait within Parallel Planes" at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2021

Taj Matumbi "Self Portrait within Parallel Planes" at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2021

Taj Matumbi - installation view of Self-Portrait within Parallel Planes at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2021

Self-Portrait within Parallel Planes

My identity forces me to live in between place and space where the imaginary and the real collide. In this series Self Portrait within Parallel Planes, I paint interlocking and overlapping figures that draw into question the boundaries between individual and collective space. Over the last four years, I have developed a painting vernacular made up of iconography that falls between these two junctions.

In exploring inbetweenness, duality of self and the multiple emerged as conceptual parameters for this exhibition. The multiple is a constant change that affects us all, but on a more personal level as a biracial person, I subconsciously and consciously project a version of myself that is fitting to the context of a space. Some refer to this as code-switching or even “passing” which leaves the individual between a space of reality and fiction.

In this body of work, I delve into repetition, motif, and movement through the framework of the multiple to explore narratives surrounding my biography, shadows of myself, and inbetweenness. I grew up skateboarding from a young age in Northern California. Skateboarding was one of my first forms of self-expression. It taught me skills and gave me tools that would later transfer to my painting process. As a skater, I learned the importance of commitment, style, and speed. I approach painting the same way I approached skateboarding, but instead of doing a hundred kickflips, I make multiple versions of the same painting, striving for consistency while embracing variation, in the way each landed kickflip looks both different and the same.

I often feel othered in any given space due to my background and identity, which often contradict assumptions. While I’ve enjoyed many privileges like studying abroad in India or going to grad school for fine art, I also grew up on welfare, and would sometimes busk by doing skateboard tricks for people at my local farmers’ market so my brothers and I could scrounge up enough money for burritos. These are a few biographical examples that highlight the paradoxical nature of my existence.

These contradictions often make me think about possible versions of myself that I am not aware of, and how feeling in between reality and fiction can give airtime to darker aspects of myself often manifesting in forms of self-doubt and sometimes masochism. Carl Jung speaks of shadows as being an unconscious aspect of yourself that can be harmful when left unchecked or ignored. I titled this series of paintings Self Portrait within Parallel Planes to acknowledge my fragmented self and to find healing.

- Taj Matumbi, 2021

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Grey Scale)", 2021

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Grey Scale)", 2021

Taj Matumbi

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Grey Scale)

2021

acrylic and oil stick on canvas

installed approx. 72 by 98 in. (ca. 182,9 by 248,9 cm)

diptych, each individual element approx. 72 by 48 in. (ca. 182,9 by 121,9 cm)

private US collection

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Beverly Hills Hunting)

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Beverly Hills Hunting)

Taj Matumbi

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Beverly Hills Hunting)

2021

acrylic and oil stick on canvas

installed approx. 72 by 98 in. (ca. 182,9 by 248,9 cm)

diptych, each individual element approx. 72 by 48 in. (ca. 182,9 by 121,9 cm)

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (North West Pacific)", 2021

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (North West Pacific)", 2021

Taj Matumbi

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (North West Pacific)

2021

acrylic and oil stick on canvas

installed approx. 72 by 98 in. (ca. 182,9 by 248,9 cm)

diptych, each individual element approx. 72 by 48 in. (ca. 182,9 by 121,9 cm)

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Miami Vice)", 2021

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Miami Vice)", 2021

Taj Matumbi

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Miami Vice)

2021

acrylic and oil stick on canvas

installed approx. 72 by 98 in. (ca. 182,9 by 248,9 cm)

diptych, each individual element approx. 72 by 48 in. (ca. 182,9 by 121,9 cm)

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Rights of Passage)", 2021

Taj Matumbi "Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Rights of Passage)", 2021

Taj Matumbi

Self-Portrait with Parallel Planes (Rights of Passage)

2021

acrylic and oil stick on canvas

installed approx. 72 by 98 in. (ca. 182,9 by 248,9 cm)

diptych, each individual element approx. 72 by 48 in. (ca. 182,9 by 121,9 cm)

Lorraine O'Grady

Lorraine O'Grady "Art Is... (Woman with Stripes", 1983-2009

Lorraine O'Grady "Art Is... (Woman with Stripes", 1983-2009

Lorraine O'Grady

Art Is...

(Woman with Stripes)

1983 / 2009

chromogenic color print, #1/8 of an edition of 8+1AP

approx. 16 by 20 in. (ca. 40,6 by 50,8 cm)

© Lorraine O’Grady/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

provenance: Alexander Gray Associates, New York

private US collection

Over the course of more than three decades, artist and cultural critic Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934 in Boston, Massachusetts to Jamaican parents) has won acclaim for her installations, performances and texts addressing the subjects of diaspora, hybridity and Black female subjectivity. Born in Boston in 1934 and trained at Wellesley College and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop as an economist, literary critic and fiction writer, O’Grady had careers as a U.S. government intelligence analyst, a translator and a rock music critic before turning her attention to the art world in 1980.

In her landmark performance Art Is…, O’Grady entered her own float in the September 1983 African-American Day Parade, riding up Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue) with fifteen collaborators dressed in white. Displayed on top of the float was an enormous, ornate gilded frame, while the words “Art Is…” were emblazoned on the float’s decorative skirt. At various points along the route, O’Grady and her collaborators jumped off the float and held up empty, gilded picture frames, inviting people to pose in them. The joyful responses turned parade onlookers into participants, affirmed the readiness of Harlem’s residents to see themselves as works of art, and created an irreplaceable record of the people and places of Harlem some thirty years ago. These color slides were taken by various people who witnessed the performance, and were later collected by O’Grady to compose the series.

Art Is. . ., a joyful performance in Harlem’s African-American Day Parade, September 1983, was, from the point of view of the work’s connection with its audience, O’Grady’s most immediately successful piece. It’s impetus had been to answer the challenge of a non-artist acquaintance that “avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with black people.” O’Grady’s response was to put avant-garde art into the largest black space she could think of, the million-plus viewers of the parade, to prove her friend wrong. It was a risk, since there was no guarantee the move would actually work. As a black Boston Brahman cum Greenwich Village bohemian, with roots in West Indian carnival, for O’Grady the Harlem marching-band parade was alien territory. But the performance was undertaken in a spirit of elation which carried over on the day. Unlike the disappointment she’d felt with Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and The Black and White Show, this piece was to be about art, not about the art world. . . rather than an invasion, it was more a crashing of the party.

Although she had received a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts to do the piece, she decided not to broadcast it to the art world. She wanted to it to be a pure gesture, she told friends, in the style of Duchamps (whose work she had been teaching at SVA for several years). But this may also have been insulation against further frustration, a way to strengthen the sense of freedom.

© Lorraine O’Grady/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

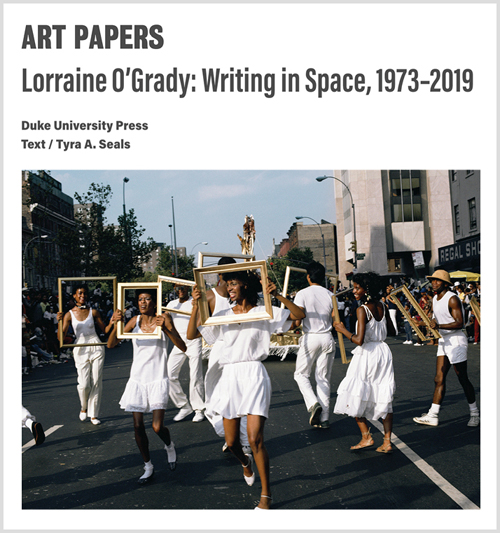

click on image to read Tyra A. Seals' book review on ArtPapers.org

click on image to read Tyra A. Seals' book review on ArtPapers.org

click on above image to read Tyra A. Seals' book review on ArtPapers.org

please contact Alexander Gray Associates to learn more about Lorraine O'Grady and see available work

![]() click to visit Alexander Gray Associates

click to visit Alexander Gray Associates

Bayeté Ross Smith

Bayeté Ross Smith "Our Kind Of People (L'Oreal)", 2010

Bayeté Ross Smith "Our Kind Of People (L'Oreal)", 2010

Bayeté Ross Smith "Our Kind Of People (Kalia)", 2010

Bayeté Ross Smith "Our Kind Of People (Kalia)", 2010

Bayeté Ross Smith "Our Kind Of People (Bayeté)", 2010

Bayeté Ross Smith "Our Kind Of People (Bayeté)", 2010

Bayeté Ross Smith

Our Kind Of People

L'Oreal

Kalia

Bayeté

2010

archival lightjet prints, edition of 5+1AP

each approx. 10.5 by 50 in. (ca. 26,7 by 127 cm)

© Bayeté Ross Smith

The Our Kind Of People series examines how clothing, ethnicity and gender affect our ideas about identity, personality and character. The subjects in this work are dressed in clothing from their own wardrobes. The outfits are worn in a style and fashion similar to how that person would wear them in daily life. I have kept the lighting and facial expressions the same in each photograph, changing only the clothing and race. Devoid of any context for assessing the personality of the individual in the photograph, the viewer projects her or his own cultural biases on each photograph.

click image to ready the The New York Times article "Bayeté Ross Smith #HereIsMyAmerica"

click image to ready the The New York Times article "Bayeté Ross Smith #HereIsMyAmerica"

Bayeté Ross Smith (born 1976, NYC) is an artist, photographer, and arts educator. He holds an MFA from the California College of the Arts in San Francisco, CA. Ross Smith’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally by the San Francisco Arts Commission, Oakland Museum of California, Rush Arts Gallery, Leica Gallery, MoMA P.S.1, Deutsche Bank, Goethe Institute (Ghana), and Zacheta National Gallery of Art (Poland). His collaborative film with the Cause Collective screened at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival, and the collaborative QUESTION BRIDGE: BLACK MALES project, with artists Chris Johnson, Kamal Sinclair and childhood friend Hank Willis Thomas, has recently gained national attention.

Bayeté’s accolades include a FSP/Jerome Fellowship, as well as fellowships and residencies with the McColl Center for Visual Art, Charlotte, NC, the Kala Institute, Berkeley, CA, the Laundromat Project, New York, and Can Serrat International Art Center, Barcelona, Spain. He has also been involved in a variety of community and public art projects with organizations such as the Jerome Foundation, BRIC Arts Media, The Laundromat Project, Alternate Roots, the city of San Francisco, the Hartford YMCA and the San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency.

His photographs have been published in numerous books and magazines, including Dis:Integration: The Splintering of Black America (2010), Posing Beauty: African American Images from the 1890s to the Present (2009), Black: A Celebration of A Culture (2005), The Spirit Of Family (2002); SPE Exposure: The Society of Photographic Education Journal, among others.

As an educator, he has taught on the collegiate level and mentored youth through community based art programs. He has worked with the International Center of Photography, New York University, Parsons, the New School for Design, the California College of the Arts, and numerous K-12 and college level courses. Bayeté is currently the Associate Program Director for KAVI (Kings against Violence Initiative), a violence prevention non-profit organization in New York that has a partnership with Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn.

Leslie Smith III

Leslie Smith III "Airplane", 2012

Leslie Smith III "Airplane", 2012

Leslie Smith III

Airplane

2012

oil on canvas

approx. 26 by 26 in. (ca. 66 by 66 cm)

Leslie Smith III "Near Window", 2011

Leslie Smith III "Near Window", 2011

Leslie Smith III

Near Window

2011

oil on canvas

approx. 26 by 26 in. (ca. 66 by 66 cm)

Leslie Smith III "Bather", 2011

Leslie Smith III "Bather", 2011

Leslie Smith III

Bather

2011

oil on canvas

approx. 26 by 26 in. (ca. 66 by 66 cm)

Leslie Smith III "Gladiator", 2011

Leslie Smith III "Gladiator", 2011

Leslie Smith III

Gladiator

2011

oil on canvas

approx. 26 by 26 in. (ca. 66 by 66 cm)

Leslie Smith III

Leslie Smith III

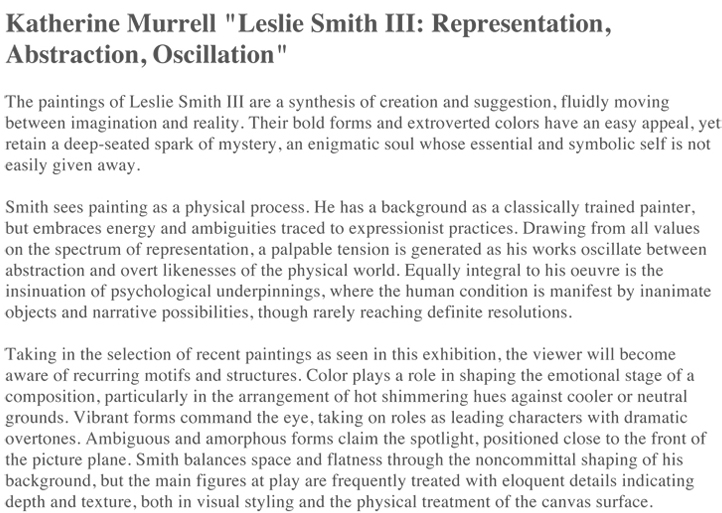

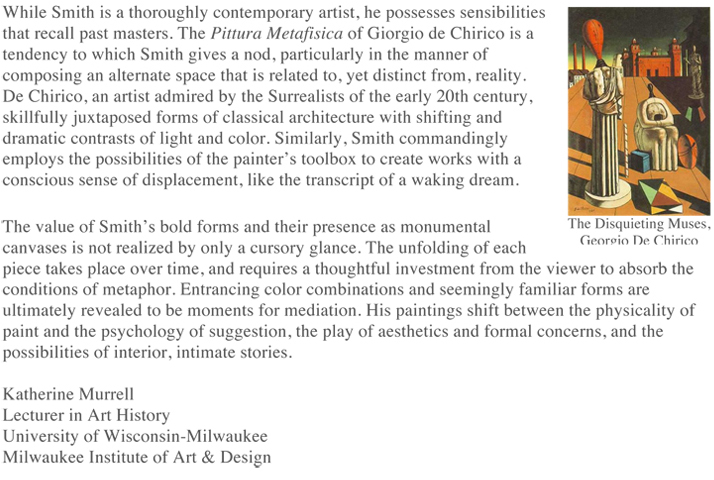

Katherine Murrell "Leslie Smith III: Representation, Abstraction, Oscillation" (excerpt)

Katherine Murrell "Leslie Smith III: Representation, Abstraction, Oscillation" (excerpt)

Katherine Murrell "Leslie Smith III: Representation, Abstraction, Oscillation" (excerpt)

Katherine Murrell "Leslie Smith III: Representation, Abstraction, Oscillation" (excerpt)

Hank Willis Thomas

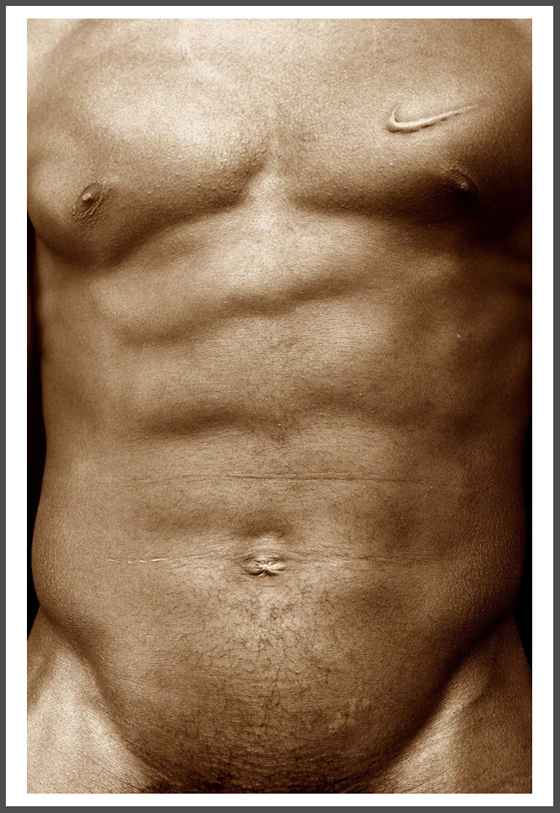

Hank Willis Thomas "Branded Chest", 2003, printed 2011

Hank Willis Thomas "Branded Chest", 2003, printed 2011

Hank Willis Thomas

Branded Chest

2003, printed 2011

digital chromogenic print, Lambda, unique

image size 40 by 30 in. (ca. 101,6 by 76,2 cm)

approx. paper size 41.5 by 30.75 (ca. 105,4 by 78,1)

© Hank Willis Thomas

provenance: Charles Guice Contemporary, the artist's studio

private US collection

Branded Chest was included in the 2018 exhibition Portraits of Who We Are at the David C. Driskell Center For The Study Of Visual Arts & Culture Of African Americans & The African Diaspora at the University of Maryland.

please contact Jack Shainman Gallery to learn more about Hank Willis Thomas and see available work

Della Wells

Della Wells "Miss Pauline", 2020

Della Wells "Miss Pauline", 2020

Della Wells

Miss Pauline

2020

acrylic on fabric, imitation fur, mixed media

approx. 18 by 14 by 7 in. (ca. 45,7 by 35,6 by 17,8 cm)

The Birthday Queen is named Miss Pauline.

She is black, beautiful, and bright.

She knows her power,

that is why she is a gleaming light.

- Della Wells, 2020

Della Wells "Miss Pauline", 2020

Della Wells "Miss Pauline", 2020

Della Wells "There Is No Fear In My Journey", 2021

Della Wells "There Is No Fear In My Journey", 2021

Della Wells

There Is No Fear In My Journey

2021

collage on canvas board

approx. 18 by 14 in. (ca. 45,7 by 35,6 cm)

Della Wells "Sulla's World", 2021

Della Wells "Sulla's World", 2021

Della Wells

Sullas's World

2021

collage on canvas board

approx. 18 by 14 in. (ca. 45,7 by 35,6 cm)