-

IRENE GRAU: ▲

November 4 - December 18, 2015

I paint to find a space. The structure integrated in this painting process exists only to show color - color, and nothing else. Color is always spread over an area, but it no longer has to be flat. And when that happens (between color and surface), it’s of essential relevance to me. That halo that exceeds the support to project elsewhere. Painting, like walking, is a process of relationship with space.

▲

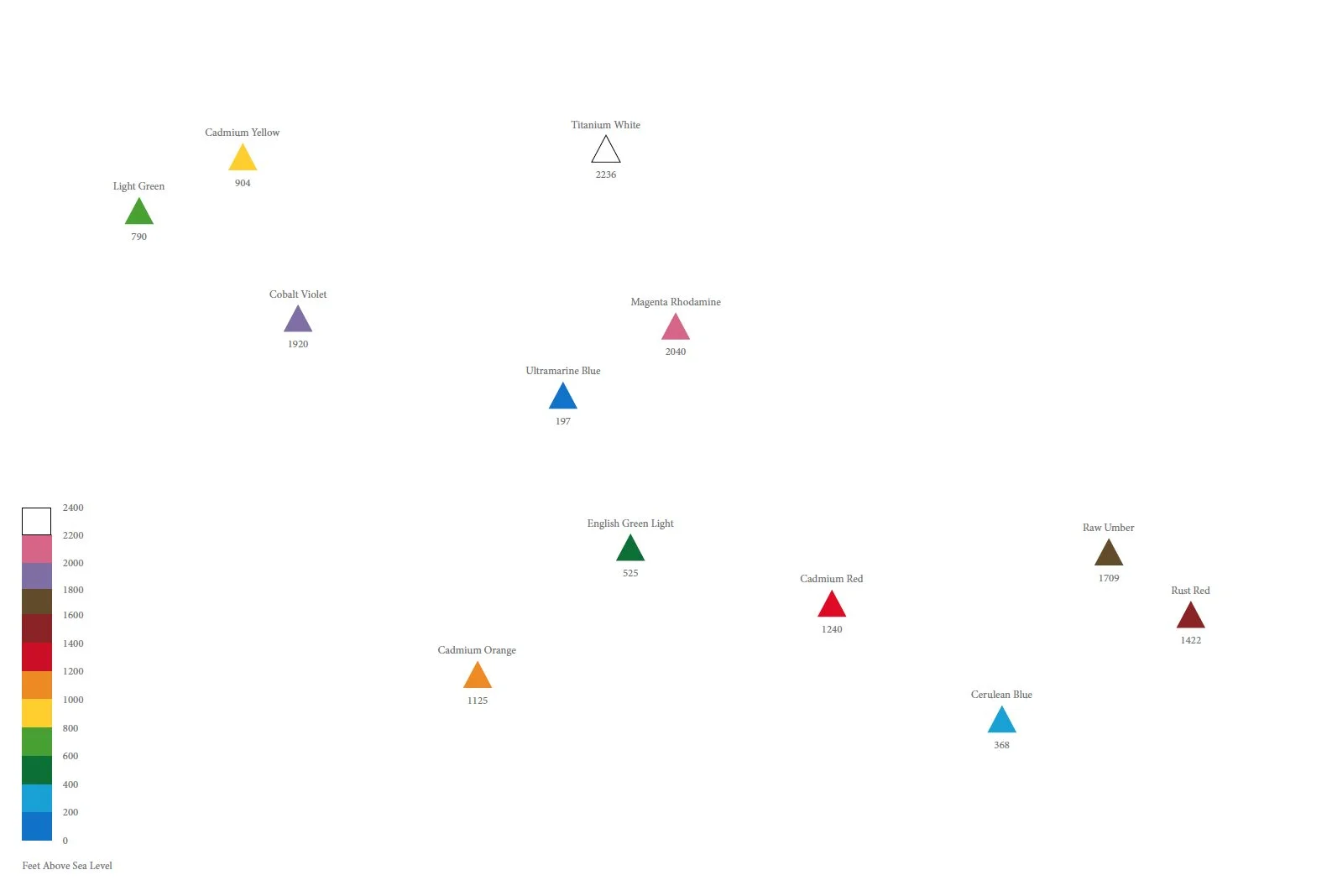

▲ is landscape. ▲ is painting. ▲ is a mountain ; a peak and its representation on the map, or simply a pile of pigment. Get out of your studio, go out, and find the painting up there, or down here. Exit and 'paint' small mountains of colored powder in different places and at different altitudes, playing with scale, color, and Altimetry. The paint loses shape or form, it returns to its formless state, and returns to the earth as a stranger, yet familiar to the landscape.

The abstract, triangular shape ▲ is both natural and artificial, it is simply the way the pigment falls into one particular place from a single point, a small action, which in turn defines the mountain and its graphical representation.

An action repeated twelve times: twelve peaks of paint.

________________

▲ = Peak

- Irene Grau, October 2015

▲ is a series of 12 photographs

Ultrachrome print on baryta-coated Ilford Gold Fibre Silk paper, mounted on 2mm dibond

edition size: 5 + 2AP

paper size: 46 by 68 cm (approx. 18.1 by 26.75 in.)

Publications

-

IRENE GRAU: GOING OUT IN SEARCH OF PAINTING

published by Irene Grau in a limited edition of 300 numbered and signed copies

october 2015

21 by 14,8 cm (approx. 8.3 by 5.8 in.)

with a text by Ángel Calvo UlloaEnglish, Spanish

saddle stitch bound softcover, 14 pages, full color

Irene Grau. Going out in search of painting.

Ángel Calvo Ulloa

The Mexican philosopher José Vasconcelos said, "traveling by foot is the fundamental measurement, the first measurement of all distances, in all civilizations".

Irene Grau goes up the mountain to paint, because her need to walk is interwined with her need to paint. She did this in her series Color Field, in which she travelled long distances by foot, carrying her art, in order to install and then photograph her works surrounded by nature, in the presence of each other. We also see this relationship in Lo que importaba estaba en la línea, no en el extremo (What Mattered Was on the Line, Not at the End), where the route she traveled determined the color and size of what was painted, and where the line defined the difficulty of the route relative to its natural topography.

To share a small digression, it is impossible not to think of Kirk Douglas when we see these paintings in the natural world. For this is how we came to know as "the mad, red-headed artist", in Vicente Minelli's Van Gogh, or perhaps through Jacques Dutronc, in the version by Maurice Pialat.

Vasconcelos also observes that "almost all other external forms in every civilization depend on the distances that one can travel by foot and the time it takes to do so". Perhaps it is in the photographic record where we, the spectators, form a vague idea of what the artist´s experience has been, of painting in the studio, and then of beginning a journey which restores them to a natural setting. It could be that Grau´s journey is a reverse journey, which reminds us of a canvas painted en plein air that returns home under the artist´s arm. It would not be so far-fetched to say that the painting of a precise historic moment is measured by the length of an arm, literally and figuratively the length of an artist's 'reach', which allows a canvas to be transported to the chosen spot. "On the tip of the tongue, on the inclement tip of the tongue, sheer and wild, create a concert there. Bring up the instruments and the seats, but don't perform anything... Let the instruments listen, up there, to the utmost volume of the tongue..."

Irene Grau's current work is up the mountain again, creating little mounds of pigment which increase the height of the mountain itself. In each snapshot, details are given on the total height that has been scaled in order to deposit those mere 10 centimeters of pigment, which once photographed, are then removed. Again Grau takes her painting out of the studio, in this case in an original state, to situate it below a triangular form. The triangle defines the mountain itself, and it is also the graphic representation of Saussure's semiotic model that explains the composition of the linguistic sign: sign, signifier, signified. So it is not merely an incidental relationship that Grau establishes, between the image she creates, the symbol that represents it and the canonical image of the sign, in this case, the geometric shape of the triangle. How could it be anything other than the triangle?

Perejaume would say: "Put the gold back in the earth, scatter the bronze, the marble and the ivory across the mountains, so they may represent that which we most lack today: the place whence they came". In all of this, there is a returning to the source, a return to that from which landscape emerges. Irene Grau has discovered that what she wants to paint is up there, and for this reason she resolutely goes out looking for it. On the walls of the Neue Galerie in the German city of Kassel hangs Courbet's disconcerting 1862 landscape painting Meadows Close to Ornans (Prairies près d'Ornans). I cannot help but find all of Irene Grau's intention encapsuled in this work. It concedes not even a shred of human presence to give us any idea of scale, but the fresh air and the smell of grass seem to seep into the room. Courbet was a studio artist, but perhaps these meadows returned in their time, under the artist´s arm, to the place from which they were wrested. Or perhaps not.